Discover how the Nihon Shoki shaped Japan’s mythology, politics, and identity.

When we introduce Shinto shrines and the Shinto religion in Japan, we inevitably touch upon their origins and the deities enshrined within them.

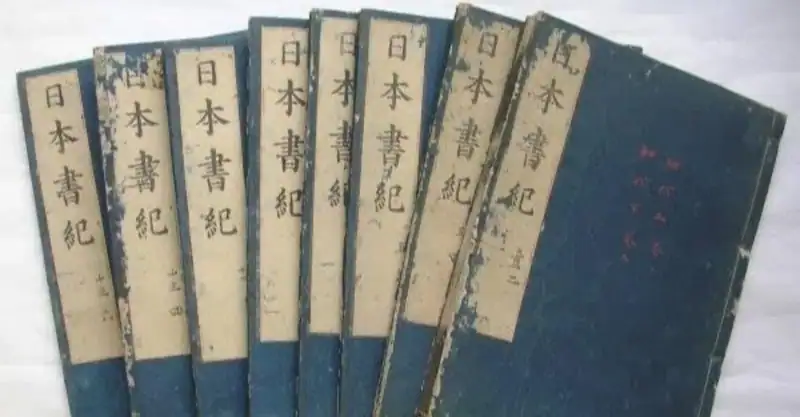

This naturally leads us to discuss ancient texts like the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki.

However, these books contain unique Japanese historical perspectives and mythology, which can be a little challenging for those from overseas.

Therefore, this time, as a key to understanding Shinto and Japanese deities, we would like to offer a simple introduction to the Nihon Shoki.

Table of Contents

The Nihon Shoki has a sibling text, the Kojiki, completed in 712 CE.

While both are primary chronicles conveying ancient Japan, they differed in their purpose of compilation.

The Kojiki primarily focused on mythology and the imperial lineage, aimed at a domestic audience, and was written in a style incorporating Japanese words (Wago).

In contrast, the Nihon Shoki was written in Classical Chinese (Kanbun), which was the international lingua franca in East Asia at the time.

It was intended, in part, to demonstrate to foreign powers, including China, that Japan was a legitimate and established state.

So, why does this over 1300-year-old chronicle still hold significance in the modern era?

In this article, we will explore the lasting impact the Nihon Shoki has continued to have on Japanese culture, spirituality, and national identity.

Nihon shoki and Kojiki

The compilation of the Nihon Shoki was not just an act of historical record-keeping; it was a profound political statement.

Commissioned by Emperor Tenmu during a period of state formation and power consolidation (the establishment of the Ritsuryo system, a legal and administrative code modeled on Chinese systems), the project aimed domestically to establish the legitimacy of the imperial line and the narrative of the nation’s origins.

Externally, particularly during a turbulent period in East Asia, it sought to present Japan as a sophisticated, historically grounded state capable of standing alongside China.

Thus, the Nihon Shoki can be seen as a tool of early Japanese diplomacy and state branding, utilizing history and mythology as cultural capital.

It was part of an effort to establish Japan’s status on the international stage, alongside the adoption of the new national name, “Nihon.”

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the Nihon Shoki, despite being an “official history” (Seishi), includes multiple variant accounts (iden, literally “different traditions”) for key mythological events, often introduced with the phrase “Another writing says…” (Issho iwaku).

This suggests an attempt not to impose a single, absolute truth but rather to integrate, or at least acknowledge, the diverse existing oral traditions and clan-specific myths.

The compilers, notably Prince Toneri, may have been less mere scribes and more editors and negotiators balancing the need for a unified narrative with the reality of diverse traditions.

This editorial approach makes the Nihon Shoki a richer and more complex source for understanding the breadth of ancient Japanese beliefs.

While the official narrative is presented, the echoes of other voices are not entirely suppressed.

The Grand Overture: A Journey Through the Nihon Shoki’s Epic

The Nihon Shoki is a sprawling chronicle spanning 30 volumes, moving from the Age of Gods (Jindai) to the reigns of human emperors.

Its contents range from the beginning of the cosmos to the formation of the state and the deeds of successive emperors.

The Dawn of the Cosmos: Heaven and Earth Separate (Tenchi Kaibyaku)

The Nihon Shoki‘s description of the world’s beginning starts from a state of chaos, followed by the separation of heaven and earth (Tenchi Kaibyaku).

This differs from the Kojiki, which begins by describing Takamahara (The High Plain of Heaven, the realm of the gods) as if it already existed.

In the Nihon Shoki, formless deities like Kuninotokotachi no Kami first appear, followed by seven generations of gods called the Seven Generations of the Age of Gods (Kamiyo Nanayo).

Finally, Izanagi no Mikoto and Izanami no Mikoto are born.

It is noted that the narrative of this creation story may show influences from Chinese Yin-Yang philosophy.

This theme of order emerging from chaos resonates with the political project of unifying the land by the Yamato court, suggesting that the divine ordering of the cosmos serves as a sacred precedent for the imperial ordering of the earthly realm.

The Deities Who Shaped Japan: Izanagi and Izanami

Standing on the Heavenly Floating Bridge (Ama no Ukihashi), Izanagi and Izanami stir the chaotic lower world with the Heavenly Jeweled Spear (Ame no Nuboko), creating Onogoro Island.

This marks the beginning of their creation of the land (Kuniumi), as they successively give birth to the islands of Japan (known as the Great Eight Island Country, Oyashima no Kuni), starting with Awaji Island.

Subsequently, they give birth to numerous gods through the birth of the gods (Kami-umi). However, when giving birth to Kagutsuchi, the god of fire, Izanami suffers burns and dies, journeying to the Land of Yomi (Yomi no Kuni), the underworld or land of the dead.

Izanagi visits Yomi to try and reclaim his beloved wife but sees her greatly changed, decaying form. By breaking a taboo, they are separated forever at the Slope of Yomi (Yomotsu Hirasaka).

This episode explains the origin of life and death.

Upon returning from Yomi, Izanagi performs a ritual purification (Misogi).

From his left eye, Amaterasu Omikami is born; from his right eye, Tsukuyomi no Mikoto; and from his nose, Susanoo no Mikoto.

These three are known as the Three Noble Deities (Mihashira no Uzunomiko).

The episodes of Izanami’s death and the Land of Yomi are not just dramatic stories but are crucial for establishing core concepts in Shinto: death, defilement (kegare), and purification (misogi harai) by exorcism and purification.

This sequence of events emphasizes a worldview where maintaining purity is essential for the appearance and regeneration of sacred power, forming the basis for Shinto purification rituals that continue to this day.

Photo: Wikipedia

From Gods to Emperors: The Human Realm

The narrative of the Nihon Shoki transitions from the Age of Gods (Jindai) to the Age of Humans (Jindai), detailing the descent of Ninigi no Mikoto, a descendant of Amaterasu Omikami, to the earth (Tenson Korin, the Descent of the Heavenly Grandson).

His descendant, Emperor Jinmu, is recorded as the first emperor, who began the rule of Japan.

The book records events up to the reign of the 41st emperor, Empress Jito.

A notable feature of the Nihon Shoki is its presentation of one or more “Another Writing Says” (Issho) or variant accounts for significant mythological events, in addition to the main text.

This wasn’t merely for academic completeness but likely reflects the political reality of integrating diverse clan myths and their ancestral deities into a grand narrative centered on the Yamato court.

By including these variant accounts, the Nihon Shoki may have been able to gain wider acceptance and skillfully incorporate different traditions.

Thus, the Nihon Shoki is not a monolithic text imposing a single story but a complex tapestry woven from multiple threads, serving as a valuable resource for understanding the diversity of ancient Japanese beliefs.

A Pantheon of Personalities: Gods and Their Exploits in the Nihon Shoki

The deities appearing in the Nihon Shoki are not merely static symbols; they are depicted as vibrant beings with distinct personalities and powerful agency.

Their stories are filled with human-like emotions and conflicts, alongside deeds of epic scale.

Amaterasu Omikami: The Radiant Sun Goddess

Amaterasu Omikami is the supreme deity of Takamahara (High Plain of Heaven) and a symbol of order, light, and legitimacy.

She is also revered as the ancestral deity of the Imperial Household.

While majestic and powerful, she also possesses a sensitive side, as seen when she hid in the Heavenly Rock Cave (Ama no Iwato) out of anger or sadness.

Born from Izanagi’s left eye, Amaterasu Omikami gave birth to many deities through a pledge (ukei) with her brother, Susanoo no Mikoto.

However, angered by Susanoo’s violent behavior, she hid in the Heavenly Rock Cave, plunging the world into darkness.

Through the earnest efforts of other deities and the dance of Amenouzume no Mikoto, Amaterasu Omikami finally reappeared from the cave, bringing light back to the world.

This story illustrates not only Amaterasu Omikami’s immense power but also her emotional depth and the importance of community effort for restoring order.

Susanoo no Mikoto: The Tempestuous Storm God

Susanoo no Mikoto, the brother of Amaterasu Omikami, is associated with the sea, storms, and the underworld.

His personality is wild and impulsive, yet he also carries deep sorrow, embodying both destruction and heroic deeds.

His repeated violent acts in Takamahara (such as destroying rice fields and defiling sacred halls) caused Amaterasu Omikami to hide, leading to his expulsion from heaven.

He descends to the land of Izumo (modern-day Shimane Prefecture).

There, he performs the heroic feat of slaying Yamata no Orochi, an eight-headed, eight-tailed giant serpent, to save Kushinada-hime.

At this time, he discovered the Kusanagi Sword in the serpent’s tail.

Afterward, he is said to have settled in Izumo and had many descendants.

Ookuninushi no Kami: Ruler of the Earth

Ookuninushi no Kami is the central deity of the Izumo mythology, known for his perseverance, kindness (illustrated, for instance, in the story of the White Hare of Inaba, more prominent in the Kojiki, though his compassionate nature is suggested), and ultimately his role as the ruler of Ashihara no Nakatsukuni, the Central Land of Reed Plains (the earthly world).

He has many alternative names, such as Oonamuchi no Kami, reflecting his complex origins and varied roles.

He overcame persecution and trials from his many brother deities known as the Eighty Deities (Yasogami).

He married Sususeribime no Mikoto, daughter of Susanoo.

Together with Sukuna-bikona no Kami, he engaged in land-building (Kunizukuri), spreading knowledge of medicine and agriculture.

Eventually, he yielded Ashihara no Nakatsukuni in the “Transfer of the Land” (Kuniyuzuri) to the deities of Amaterasu Omikami’s lineage, and in return, he was enshrined at the magnificent Izumo Taisha shrine.

This was a crucial event linking the rule of the heavenly deities with earthly governance.

Ninigi no Mikoto: Grandson of Amaterasu

Ninigi no Mikoto, grandson of Amaterasu Omikami and Takamimusubi no Kami, was chosen to descend from heaven to rule Japan.

This symbolizes the direct divine commission of the Imperial Household’s rule.

In this event, known as Tenson Korin (the Descent of the Heavenly Grandson), Ninigi no Mikoto descended to the peak of Mt. Takachiho in Hyuga (modern-day Miyazaki Prefecture) carrying the Three Sacred Treasures (Sanshu no Jingi: the mirror, sword, and jewel), accompanied by many other deities.

There, guided by the earthly deity Sarutahiko no Kami, he married Konohana-sakuya-hime, daughter of the mountain deity Ooyamazumi no Kami.

The story of this marriage and his choice not to marry her older sister, Iwanaga-hime, explains why the emperors’ lives are fleeting like cherry blossoms and not eternal like rocks.

Ninigi no Mikoto is the direct ancestor of Emperor Jinmu, Japan’s legendary first emperor.

Yamato Takeru no Mikoto: The Tragic Hero

Prince of Emperor Keiko, Yamato Takeru no Mikoto is a hero renowned for his immense martial prowess and tragic destiny.

His story is one of conquest and sorrow.

In his campaigns, he conquered the Kumaso (in Kyushu) by disguising himself as a woman to assassinate their leader and the Ezo (in eastern Japan), for which he was granted the Kusanagi Sword by his aunt, Yamato-hime no Mikoto, at Ise Shrine.

However, during his eastern expedition, his wife, Otachibana-hime no Mikoto, sacrificed herself by jumping into the raging sea to calm it.

Ultimately, he fell ill after disrespecting the deity of Mt. Ibuki and died.

The legend says he transformed into a white bird and flew away (Shiratama Densetsu, the White Bird Legend).

Photo: Wikipedia(Amaterasu)

Here is a summary table of these key deities:

| Deity (Kami) | Primary Domain/Traits | Defining Moment in Nihon Shoki | Enduring Legacy/Notable Shrines |

| Amaterasu Omikami | Sun, Order, Ancestor of Imperial Line | Hiding in the Heavenly Rock Cave & Return | Ancestral Deity of Imperial House / Ise Grand Shrine |

| Susanoo no Mikoto | Storms, Sea, Heroism & Destruction | Slaying the Yamata no Orochi | Heroic Deity of Izumo region / Yasaka Shrine etc. |

| Ookuninushi no Kami | Earthly Rule, Land-building, Matchmaking | Transfer of the Land (Kuniyuzuri) | Deity of Land-building, Matchmaking / Izumo Taisha |

| Ninigi no Mikoto | Heavenly Grandson, Founder of Imperial Line’s Earthly Rule | Descent of the Heavenly Grandson (Tenson Korin) | Direct Ancestor of Emperors / Takachiho Shrine, Kirishima Jingu etc. |

| Yamato Takeru no Mikoto | Hero, Conquest, Tragedy | Eastern Campaign & Otachibana-hime’s Sacrifice, White Bird Legend | Tragic Hero / Various sites associated with Yamato Takeru, Shiratori Shrine etc. |

The human-like emotions and flaws seen in the stories of these deities depict them not as mere abstract beings but as complex, relatable characters.

Amaterasu Omikami’s anger and fear, Susanoo no Mikoto’s jealousy and recklessness, Ookuninushi no Kami’s hardships and patience all show that the gods possessed feelings similar to humans, making their stories more engaging.

This “humanity” of the gods may reflect the ancient Japanese worldview where the divine and human realms were more closely intertwined.

Furthermore, particularly in the stories surrounding Susanoo no Mikoto, the theme of the conflict between order (Amaterasu Omikami, the heavenly gods, agricultural culture) and chaos (Susanoo’s wildness, untamed nature, uncivilized lands) is prominent.

The narrative where Susanoo disrupts the order of Takamahara and, as atonement, slays the symbol of chaos, the Yamata no Orochi, can be interpreted as symbolizing the process of civilization.

The conflicts and resolutions among these deities also function as allegories about human societal dynamics and how to interact with nature, while also serving to legitimize the Yamato court’s efforts to pacify and unify the land as a continuation of the cosmic establishment of order.

Resonance Across Time: How the Nihon Shoki Forged Japan’s Soul

The Nihon Shoki is more than just an ancient record; it has etched a profound influence on every aspect of modern Japan, from the imperial line and faith to values and the arts.

Imperial Lineage and National Identity

The Nihon Shoki‘s depiction of the unbroken line of emperors (Manshin Ikkei), originating from Amaterasu Omikami, has formed the bedrock of the Imperial Household’s legitimacy and Japan’s national identity.

This narrative was used, particularly during periods of national unification or crisis, to bolster the Emperor’s authority and the concept of the Kokutai , or national polity/essence.

The Divine Mandate of Eternal Duration (Tenjō Mukyū no Shinsō) and, in certain historical periods, the idea of the Emperor as a Living God (Arahitogami) are prime examples.

Sacred Sites and Living Traditions: Shrines and Festivals

Many Shinto shrines trace their origins or enshrined deities back to events and figures in the Nihon Shoki.

Ise Grand Shrine enshrining Amaterasu Omikami, Izumo Taisha enshrining Ookuninushi no Kami, and Atsuta Shrine housing the Kusanagi Sword are prominent examples, but countless smaller shrines across the country are also deeply connected to these ancient narratives.

Similarly, many festivals (matsuri) either reenact mythological events recorded in the Nihon Shoki or offer thanks to the deities.

The springtime Kinensai praying for a good harvest and the autumn Niinamesai giving thanks for the harvest are deeply intertwined with imperial rituals and the agricultural cycle, with origins dating back to antiquity.

The story of the Heavenly Rock Cave is considered the prototype of Kagura, ritual dances performed in Shinto.

Cultural DNA: Values, Ethics, and Artistic Expression

The Nihon Shoki has also contributed to the formation of traditional Japanese values.

Examples include the spirit of “harmony” (wa), epitomized in Prince Shotoku’s Seventeen-Article Constitution (attributed to him), which states “Harmony is to be valued”; the concept of “purity” (seijō) seen in Izanagi’s ritual purification; “loyalty” (chūsei) to the Emperor; and “ancestor worship” (sosen sūhai) reflected in the imperial lineage.

These narratives provide foundational stories for understanding good conduct, responsibility, and the consequences of actions, influencing ethics and morality.

Its influence on traditional arts is also significant.

In Noh theater, numerous plays take themes from Nihon Shoki myths and legends, such as “Kamo,” “Miwa,” and “Iwato” (Heavenly Rock Cave).

In Kabuki, works like “Nihon Furisode Hajime” (based on the Yamata no Orochi myth) and “Yamato Takeru” transmit ancient stories to the modern era.

In the realm of painting, from Yamato-e (traditional Japanese painting style) to Ukiyo-e (woodblock prints), artists like Kobayashi Eitaku and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi have depicted scenes from the Nihon Shoki.

Stories That Still Teach: Governance and Human Drama

The anecdote of Emperor Nintoku and the “People’s Hearths” (Tami no Kamado) is well-known as a story symbolizing the benevolence and compassionate governance of a ruler towards the populace.

This story contains timeless lessons about the ideal conduct of leadership.

Furthermore, the Seventeen-Article Constitution attributed to Prince Shotoku in the Nihon Shoki describes ethical guidelines for officials and principles of governance, emphasizing harmony, duty, and justice. Many of these principles still resonate in discussions about ideal governance and social behavior today.

Stories like Emperor Sujin quelling a plague and sending generals (Shido Shogun) to establish order, or the tragic tale of a hero like Yamato Takeru, also appeal to modern readers as compelling human dramas.

Considering these influences, the narratives of the Nihon Shoki and the values embedded within them have served as a sort of foundational programming language for many aspects of Japanese culture that followed.

Just as the imperial mythology directly supports Shinto rituals centered on the imperial ancestors, these elements are interconnected components of a cultural system, not isolated influences.

This “source code” nature means that understanding the Nihon Shoki is key to unlocking deeper meaning in many later expressions of Japanese culture.

However, the stories and lessons of the Nihon Shoki are not static; they have been reinterpreted and adapted to suit the needs and sensibilities of each era.

For example, just as the Seventeen-Article Constitution influenced later legal codes and Noh and Kabuki adapted ancient myths for new audiences, this text has been in constant dialogue with society.

This continuous engagement with the past is a crucial aspect of cultural identity.

Moreover, the Nihon Shoki seamlessly blends what might be distinguished in modern sensibility as mythology (the Age of Gods) and history (the reigns of emperors).

For the compilers and their intended audience, this was not an awkward transition but a continuous narrative establishing the divine origins of secular authority.

This structure reinforces the idea that imperial rule was not merely a political construct but a sacred commission rooted in the very fabric of the cosmos.

This fusion of myth and history is a key characteristic of how early states often legitimized themselves and challenges modern attempts to neatly separate “myth” and “fact” when analyzing such foundational texts.

The Enduring Magic of the Nihon Shoki: Why This Ancient Chronicle Still Captivates

The Nihon Shoki retains its importance today as a grand narrative, featuring a memorable pantheon of gods and acting as a profound shaper of Japanese civilization.

Universal themes of creation, heroism, love, betrayal, sacrifice, the quest for order, the relationship between the human and the sacred, and the nature of leadership are sources of its lasting appeal.

Even in a secularized modern society, these ancient stories continue to offer insights into human nature and cultural identity.

They provide a sense of connection to a deep past.

Despite its age, the Nihon Shoki remains an object of academic study and popular interest, revealing new layers of meaning as society evolves and new analytical perspectives are applied.

Debates continue, for example, about the historicity of Emperor Jinmu or the authenticity of the Seventeen-Article Constitution, and it is referenced to understand everything from ancient epidemics to modern business ethics.

This continued engagement demonstrates its richness and complexity.

The very act of reading the Nihon Shoki is a cultural practice that connects modern Japan to its ancient past, serving as a mirror reflecting current concerns and values back onto the foundational narratives, ensuring its “living” quality.

Exploring the world of the Nihon Shoki can be a richer experience through visiting related shrines, reading modern translations, or enjoying artistic adaptations.

This ancient chronicle still speaks volumes to us about our roots and the universal drama of human existence.

Leave a Reply