Welcome to the World of Onomatopoeia that Colors the Japanese Language

One of the expressions that richly colors the Japanese language is “onomatopoeia.”

Onomatopoeia is a general term for words that mimic sounds, known as giongo (擬音語), words that depict states or movements, known as gitaigo (擬態語), and even words that express emotions, called gijoogo (擬情語).

Our daily lives are, in fact, overflowing with onomatopoeia.

Table of Contents

[related_posts_by_tag

For example, when describing physical discomfort.

A sharp pain is zukizuki (ズキズキ), a burning sensation like a scald is hirihiri (ヒリヒリ), a pricking pain like a needle is chikuchiku (チクチク), an electric shock-like sensation is piripiri (ピリピリ), and a splitting headache is gangan (ガンガン).

These words are far more specific and evocative than simply saying “it hurts.”

The depiction of nature is similar.

The sound of rain fiercely beating a_g_ainst the ground is zaazaa (ザーザー), while a scene of rain falling quietly and persistently is shintoshinto (しとしと).

These onomatopoeic expressions can convey the very atmosphere of a place just by hearing the words.

| Onomatopoeia | Explanation |

| Zaazaa | Heavy, intense rainfall |

| Shitoshito | Rain falling quietly and persistently |

| Potsupotsu | Rain starting to fall sparsely, a few drops |

| Parapara | Light, scattered raindrops falling |

In this article, we will explore the historical background of such Japanese onomatopoeia, delving into when they began to be used.

We will also examine their crucial role in our daily lives and in Japanese language acquisition, particularly in situations like conveying pain to a doctor at a hospital. Furthermore, we will introduce, with concrete episodes, how non-native Japanese speakers approach and perceive these unique expressions.

It’s often said that Japanese has three to five times more onomatopoeia than Western languages.

This fact may suggest the unique linguistic characteristics of Japanese and the depth of Japanese culture.

So, let’s peer into the kaleidoscopic world of onomatopoeia together.

Tracing the Roots of Onomatopoeia: When Did They Start Being Used?

Japanese onomatopoeia are not new words born in modern times.

Their history is ancient, tracing back to Japan’s oldest written records.

These words are precious “linguistic fossils” that convey the lives and sensations of ancient people to the present day, and at the same time, they are “living words” that continue to change with the times.

Ancient Sounds in Myths and Poetry

One of the oldest examples of onomatopoeia can be found in the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters), Japan’s oldest historical text, compiled in 712 AD.

In the creation myth, when the deities Izanagi-no-Mikoto and Izanami-no-Mikoto stir the chaotic earth with the Ame-no-nuboko (heavenly jeweled spear), the action is described as koworo-koworo (こをろこをろ).

This koworo-koworo is interpreted as being close to modern expressions like kururi-kururi (くるりくるり) or korokoro (ころころ), which describe the sound or motion of something rotating or being stirred.

It is fascinating that such a grand mythological scene is narrated with such a concrete sound image.

The Man’yoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), Japan’s oldest anthology of poems compiled in the Nara period (710-794 AD, completed around 759 AD), also features numerous onomatopoeia.

For instance, there is a poem that describes a crow’s caw as koroku (ころく).

Other examples include i (い) for a horse’s neigh, sayasaya (さやさや) for the faint rustling sound of objects rubbing together, and futsuni (ふつに) for the sound of striking something hard.

These expressions vividly convey the daily lives and views of nature held by people of that era.

The fact that these onomatopoeia are frequently found in poetic tales and waka poems, which are considered close to spoken language, suggests a process where words actively used in conversation were later recorded in writing.

Onomatopoeia Changing with the Times

Onomatopoeia have changed in meaning and usage over time.

Looking at documents from the Heian period (794-1185 AD), the word honobono (ほのぼの) shows an interesting transition.

Initially, honobono to was primarily used to describe the faint light around dawn.

However, as time went on, its usage expanded to encompass the light of the moon, the twilight of evening, and even the warmth of human emotions.

By the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185-1573 AD), examples of its use to describe scenes other than dawn increased.

In the Edo period (1603-1868 AD), the scholar of classical Japanese literature, Motoori Norinaga, left behind his considerations on the interpretation of this honobono when annotating classics.

Entering the Meiji period (1868-1912 AD), influenced by Western linguistics, the study and classification of onomatopoeia began in earnest.

Amidst the genbun itchi movement (a movement to unify spoken and written language), onomatopoeia were actively incorporated into modern literature.

From around this time, the French-derived term “onomatopoeia” began to be used alongside or in place of traditional Japanese terms like giseigo (擬声語 – mimetic words for voices/sounds).

Thus, even the term referring to onomatopoeia itself has changed, reflecting shifts in academic perspectives and international scholarly exchange.

Japanese Sensibility and View of Nature

One reason pointed out for the striking abundance of onomatopoeia in Japanese is the cultural background where Japanese people have, since ancient times, possessed a deep sensitivity to the sounds and scenes of nature, striving to express them in words.

For example, while some cultures may perceive insect sounds as “noise,” in Japan, there is a custom of distinguishing them as “pleasant sounds” and giving them individual names to enjoy.

Such delicate sensibilities, nurtured in a life symbiotic with nature, may have given birth to a rich vocabulary of onomatopoeia.

Looking back at the history of onomatopoeia, it becomes clear that they are not mere wordplay but are deeply connected to the Japanese worldview, aesthetic sense, and ways of communication.

From ancient myths to modern daily conversation, onomatopoeia continue to enrich the expressive power of the Japanese language.

Why Are Onomatopoeia Important?

Their Role in Japanese Language Acquisition and Daily Life

Onomatopoeia play a role more significant than mere decorative words in Japanese communication.

This is because they possess the power to give vivid realism to language and to accurately convey subtle nuances and emotions.

While they represent a hurdle for non-native Japanese speakers, understanding and mastering them can open the door to more natural and richer Japanese expression.

Classifying Onomatopoeia that Enrich Expression

Onomatopoeia can be divided into several types based on their function:

- Giongo (擬音語)

Words that imitate actual sounds, such as thunder rumbling gorogoro (ゴロゴロ) or knocking on a door tonton (トントン).

Those representing animal sounds, like wanwan (ワンワン) for a dog’s bark or nyaa (ニャー) for a cat’s meow, are sometimes specifically called giseigo (擬声語). - Gitaigo (擬態語)

Words that sensuously express states, conditions, or movements that do not necessarily involve sound.

Examples include stars sparkling kirakira (キラキラ) or a road winding kunekune (くねくね).

Within gitaigo, there are further subcategories:- Giyoogo (擬容語)

Describes actions or appearances of living beings (e.g., smiling nikoniko (ニコニコ), walking briskly sutasuta (スタスタ)). - Gijoogo (擬情語)

Expresses human emotions or mental states (e.g., heart pounding dokidoki (ドキドキ) with excitement or nervousness, feeling cheerful ukiuki (ウキウキ)).

- Giyoogo (擬容語)

These onomatopoeia enable the instantaneous communication of complex situations and emotions with short words, adding rhythm and depth to conversations and texts.

Onomatopoeia in Medical Settings: A Lifeline for Conveying Pain

The importance of onomatopoeia is particularly prominent in the expression of pain in medical settings.

When patients convey their pain to doctors, accurately describing its “quality” is extremely important for diagnosis.

Japanese onomatopoeia can depict this subjective and elusive sensation of “pain” with surprising subtlety.

For instance, even with the same “headache,” a gangan (ガンガン) pain differs in nature from a zukizuki (ズキズキ) pain.

Gangan evokes a severe, pounding pain as if the entire head is splitting, while zukizuki suggests a throbbing, periodic pain.

These expressions become crucial clues for doctors searching for the cause of the pain.

In fact, traditional East Asian medicine is said to classify pain into ten types, with corresponding onomatopoeia for each.

Even in Western medicine, onomatopoeia are considered helpful in distinguishing between inflammatory and neuropathic pain.

| Onomatopoeia | Japanese Description/Sensation | Possible Situations/Causes |

| Zukizuki | Throbbing, periodically intensifying pain | Headache, toothache, wound pain, inflammation |

| Hirihiri | Burning, scraping, persistent stinging pain on the surface | Sunburn, abrasion, light burn, mucosal inflammation |

| Chikuchiku | Light, intermittent, sharp pricking pain, like being poked with a thin needle | Sty, scratchy throat, foreign object contact |

| Piripiri | Fine, electric-like stimulation on the skin surface, or pain from spiciness like chili | Mild numbness, nerve hypersensitivity, dry skin, spices |

| Gangan | Intense, resonant pain, like a bell ringing loudly inside the head | Migraine, hangover headache |

| Kirikiri | Sharp, piercing, persistent pain, as if being gouged with something thin | Stomachache (especially stress-induced), acute abdomen |

| Shikushiku | Dull, heavy, persistent ache; also relates to the image of quiet sobbing (shikushiku naku) | Gastrointestinal discomfort, menstrual pain, dull visceral pain |

| Jinjin | Pain that resonates from within the body or feels hot, often due to numbness or inflammation | Numbness after a strong bruise, frostbite, neuralgia, progressing inflammation |

Thus, onomatopoeia function as a “common language” between patients and medical professionals for sharing the type and degree of pain.

In recent years, research is underway to quantify these delicate Japanese pain expressions and develop them as multilingual medical assessment scales, with expectations for contributions to international medical communication.

This indicates that onomatopoeia have the potential to transcend mere subjective expression and become objective diagnostic tools.

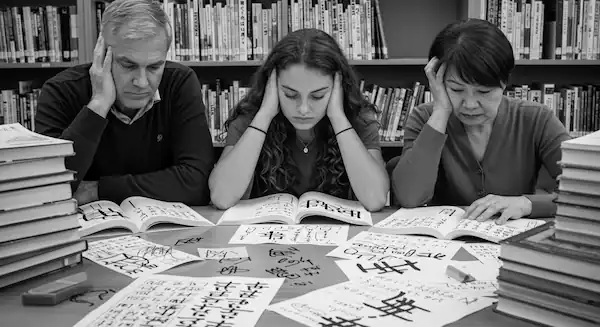

Importance for Japanese Language Learners

For Japanese language learners, acquiring onomatopoeia is an important step towards fluency.

They appear frequently not only in daily conversation but also in all kinds of Japanese media, including manga, anime, and literary works.

Understanding and being able to use them appropriately vastly expands one’s range of expression, enabling more “Japanese-like,” natural communication.

Onomatopoeia not only represent sounds and states but also convey the speaker’s emotions and bodily sensations, making it easier to create empathy.

Words like dokidoki (heart-pounding excitement/nervousness) and wakuwaku (thrilled excitement) have the power to evoke similar feelings in the listener’s heart.

Onomatopoeia are an element symbolizing the depth and expressive richness of the Japanese language, and their effective use is indispensable for achieving smooth and emotionally rich communication.

“What Does This Mean?”

The Barriers and Charms of Onomatopoeia as Seen by Foreigners

While Japanese onomatopoeia color the language with their richness and expressiveness, they often stand as a major hurdle for foreigners learning Japanese.

However, overcoming this barrier can lead to an encounter with a new charm of the Japanese language.

Difficulties of Onomatopoeia that Puzzle Learners

There are several reasons why foreign learners struggle to acquire onomatopoeia:

- Overwhelming Number

It is said that there are about 4,500 to 5,000 onomatopoeia in Japanese, a number significantly larger than English (around 1,000-1,500) or French (around 600). Simply memorizing this vast quantity is a daunting task. - Distinguishing Subtle Nuances

There are countless onomatopoeia like sarasara (smooth, dry, rustling) versus zarazara (rough), or tsurutsuru (slippery smooth) versus subesube (smooth, soft to the touch), which sound similar but have subtly different meanings or textures.

Understanding and using these fine distinctions is extremely difficult.

These differences, which are intuitive for native Japanese speakers, are hard for learners to grasp without concrete explanations or experiences.

For example, there was a case where Indonesian trainees working on a farm could not understand the soft, dry state of soil described as sarasara or fuwafuwa (fluffy).

It was only when they were shown by someone stepping on or touching the soil that they understood.

This shows that onomatopoeia are not just about word-to-word correspondence but are tied to specific sensory and cultural experiences shared by Japanese people. - High Context Dependency

The same onomatopoeia can have completely different meanings depending on the context.

For example, gorogoro can mean the rumbling of thunder, a cat purring, lazing around at home doing nothing, or the gurgling of an upset stomach.

Such polysemy is a source of confusion for learners. - Cultural Background Differences

- Hesitation About Adult Use

Some foreigners, whose native languages primarily use onomatopoeia for children, are surprised that Japanese adults frequently use them in daily conversation and may feel it is “childish.”

This is not just a linguistic difficulty but a hesitation stemming from different cultural norms regarding expression. - Difficulty of Direct Translation

Many onomatopoeia do not have a perfect one-to-one translation in other languages. Therefore, learners need to grasp the image and sensation behind the words.

- Hesitation About Adult Use

Specific Experiences of Foreigners: Confusion and Discovery

There are some interesting examples of how foreign learners react to onomatopoeia.

In one study, when English speakers who were not native Japanese speakers heard the onomatopoeia dokidoki without context, some had impressions like “so-so” or “fed up,” which differ from its original Japanese meaning (heart pounding due to excitement or tension).

However, when presented with example sentences, they reached a closer understanding, such as “nervous” or “excited.” On the other hand, when they heard the positive onomatopoeia nikoniko (smiling cheerfully) as just a sound, there were cases where they formed completely opposite, negative impressions like “vexed” or “unhappy,” showing that the sound’s resonance can connect with native language sensibilities to produce unexpected interpretations.

There’s also an anecdote about an Indonesian trainee who mistook the Japanese onomatopoeia unyuunyu (ウニュウニュ), describing the wriggling movement of a caterpillar, for a word meaning “cute” in their native language and laughed.

This is an amusing misunderstanding caused by a coincidental similarity in sound, but it simultaneously shows how differently the connection between sound and meaning in onomatopoeia can be across languages.

| Onomatopoeia | Typical Japanese Meaning | Common Foreigner Misconceptions/Impressions | Possible Reasons for Confusion |

| Dokidoki | Heart pounding due to excitement, nervousness, anxiety, etc. | “So-so,” “fed up” (without context) | Sound associations in one’s native language; lack of context. |

| Nikoniko | Smiling cheerfully or gently | “Vexed,” “unhappy” (without context) | The sound’s resonance in one’s native language might be linked to negative emotions. |

| (General) Adult Use | Commonly used by adults in daily conversation. | “Isn’t it childish language?” | In some linguistic cultures, onomatopoeia are primarily used as baby talk. |

| Sarasara/Fuwafuwa | Smooth texture / Light and soft texture | Meaning is difficult to grasp; a concrete image doesn’t come to mind. | Expresses abstract tactile sensations; difficult to understand without direct sensory experience. No single equivalent word in their native language might exist. |

| Unyuunyu | Wriggling movement, like that of a worm | (For an Indonesian speaker) Sounds like “cute.” | Coincidental similarity with a word of similar sound in another language. |

However, it’s not all difficulties.

One foreigner fluent in Japanese shared that although they were initially overwhelmed by the number and subtle nuances of onomatopoeia, they encountered words like kyun (キュン – a heart-clenching, poignant feeling) and dokidoki.

Experiencing how these words perfectly matched their own emotions and physical sensations, they were deeply moved by the expressive depth of Japanese.

For this person, onomatopoeia opened a new door to recognizing and expressing their emotions more profoundly.

Thus, once learners experience their charm, onomatopoeia can become an extremely powerful expressive tool.

Tips for Learners and Supporters

There are several points that learners can keep in mind to help with onomatopoeia acquisition, and that Japanese speakers interacting with learners can also be mindful of:

- To Learners

It’s best to start by gradually memorizing basic, commonly used onomatopoeia like zaazaa (heavy rain) and dokidoki (heart pounding).

Learning them in conjunction with illustrations, gestures, or real objects and situations will make it easier to grasp the image.

Learning methods focusing on sound symbolism (the image associated with specific sounds) are also expected to be effective, but caution is needed not to be overly influenced by the sound sensations of one’s native language. - To Japanese Speakers

When speaking with foreigners, be aware that onomatopoeia may not always be easily understood.

Sometimes, it’s important to show consideration by rephrasing with simpler words, such as saying “It’s raining a lot” instead of using an onomatopoeia.

Onomatopoeia are a source of richness in the Japanese language and, at the same time, an interesting point of contact in cross-cultural communication.

The effort to overcome this barrier and the ingenuity to assist in that effort will lead to deeper mutual understanding.

Onomatopoeia as a Symbol of the Richness of the Japanese Language

As we have seen, Japanese onomatopoeia, in their ancient history, diversity of expression, and importance in daily life, can be said to be one of the distinctive features of the Japanese language.

From the primordial sound of koworo-koworo in the ancient Kojiki to the expressions for rain sounds and pain that we casually use today, onomatopoeia have played an indispensable role in reflecting the delicate sensibilities and rich emotions of the Japanese people and facilitating communication.

Particularly in medical settings, the fact that words like zukizuki and chikuchiku accurately convey the quality of a patient’s suffering and aid in diagnosis clearly demonstrates that onomatopoeia possess practical value beyond mere emotional expression.

This is one aspect of the power of onomatopoeia to transform subjective sensations into a form shareable with others.

For foreign learners, their vast number and subtle nuances can indeed be a high wall.

Differences from their native language sensibilities may lead them to feel that “adult use is childish” or to associate completely different meanings from the sound’s resonance.

However, when they overcome that wall and become able, for example, to accurately express the heart-fluttering feeling of kyun, they can touch upon a new depth and joy of expression in Japanese.

Onomatopoeia Created in Modern Times

Interestingly, the power to create onomatopoeic words has not waned even in modern times.

Among internet slang and youth language, new expressions can be found such as jiwaru (じわる – something gradually becoming amusing), emoi (エモい – an emotionally stirring, hard-to-describe feeling), and kusa (草 – meaning “lol,” from the internet slang “www” looking like grass).

While these may not strictly fit the traditional definition of onomatopoeia, they share a common spirit in their attempt to vividly convey sensations and states with short words.

This can be seen as a manifestation of the dynamism of language, constantly changing and seeking new methods of expression.

It has also been pointed out that onomatopoeia from manga may become popular phrases and eventually establish themselves as new vocabulary.

Onomatopoeia are not merely for imitating sounds or describing states; they are like a mirror reflecting the Japanese view of nature, bodily sensations, emotional subtleties, and empathy in communication.

For those learning Japanese, they are both a challenge and a key to touching the core of Japanese culture.

We Japanese can further refine our expressive power by cherishing this rich linguistic heritage and utilizing it in our daily communication.

And we sincerely hope that those learning Japanese will, through the kaleidoscope of onomatopoeia, experience the profound charm of the language.

Words are living things, and even creating new onomatopoeia might be one way each of us participates in the evolution of language.

Reference site

- 日本語の魅力~オノマトペ – ニューヨークアカデミー講師ブログ

- よく使うオノマトペ一覧 意味と例文のリストを公開

- 雨のオノマトペ – テレビ朝日 アナウンサーズ ことばのアレコレ

- オノマトペの効果や使い方は? 擬音語・擬態語で文章を伝わりやすく – 榎本メソッド小説講座